African American literature is more than just a collection of stories—it is the chronicle of a people’s survival, resistance, creativity, and contribution to American and global culture. From its beginnings in the crucible of slavery to the dynamic works of contemporary voices, Black storytelling has continuously reshaped the nation’s understanding of freedom, justice, and identity. This journey reflects not only the lived experiences of African Americans but also their determination to assert humanity in the face of oppression and to imagine new futures through art.

The Origins: Slave Narratives and Early Writings

The roots of African American literature lie in the 18th and 19th centuries, when enslaved people began writing or dictating narratives of their lives. Figures like Olaudah Equiano (The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, 1789), Harriet Jacobs (Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, 1861), and Frederick Douglass (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, 1845) offered searing first-hand testimonies of slavery.

These narratives served multiple purposes: they bore witness to cruelty, humanized the enslaved in societies that considered them property, and rallied support for abolitionist movements. Written in a style accessible to broad audiences, they challenged dominant myths of Black inferiority. Importantly, they placed literacy and storytelling at the center of Black liberation, proving that words could be weapons of resistance.

Reconstruction and the Rise of Post-Emancipation Voices

After emancipation, African American writers turned to exploring the challenges of freedom in a hostile society. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wrote poetry and fiction addressing Reconstruction’s racial struggles. Charles W. Chesnutt, through works like The Conjure Woman (1899), combined folklore with social commentary, subtly critiquing racism in post-Civil War America.

This era also saw the growth of African American journalism and speeches that blended rhetoric, autobiography, and politics. Writers used literature as a way to negotiate identity in a society reluctant to honor Black citizenship.

The Harlem Renaissance: A Flourishing of Black Arts

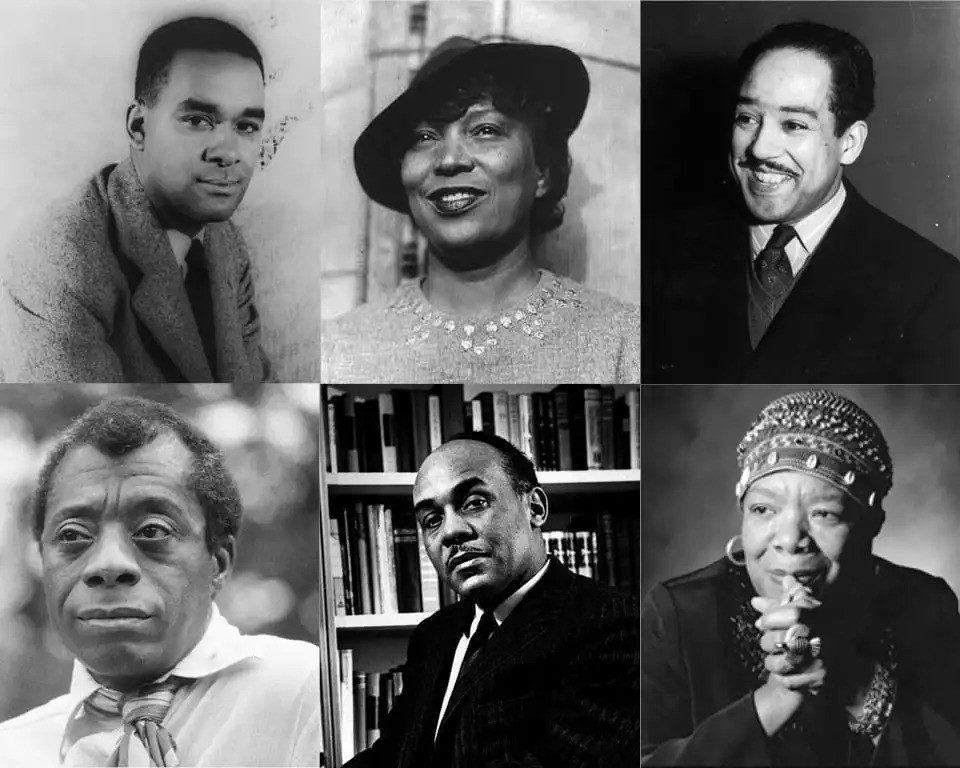

The 1920s marked a cultural explosion known as the Harlem Renaissance. Harlem, New York, became the symbolic capital of Black creativity, as poets, novelists, musicians, and visual artists converged to celebrate African American identity.

Langston Hughes, often considered the voice of the Renaissance, captured the rhythms of jazz, blues, and everyday Black life in poetry that insisted on beauty and dignity in Blackness. Zora Neale Hurston infused folklore, anthropology, and storytelling in works like Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). Writers like Claude McKay (Home to Harlem), Countee Cullen, and Nella Larsen (Passing) contributed novels and poetry that explored themes of race, migration, sexuality, and cultural pride.

This period asserted that African American literature was not merely reactive to oppression but an autonomous artistic tradition. It laid the foundation for later generations, insisting that Black experiences were central to the American story.

Mid-20th Century: Protest, Realism, and New Voices

The Great Depression, World War II, and the Civil Rights Movement influenced mid-20th-century literature. Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) exposed the systemic racism and poverty that trapped African Americans in cycles of violence and despair. James Baldwin, in essays like Notes of a Native Son (1955) and novels like Giovanni’s Room (1956), combined searing critique with lyrical prose, addressing not only race but also sexuality, morality, and faith.

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) became a landmark novel, articulating the existential struggle of Black identity in a world that refused recognition. Lorraine Hansberry’s play A Raisin in the Sun (1959) brought African American family life and dreams of social mobility to the Broadway stage, becoming a cultural milestone.

During this time, African American literature was deeply intertwined with social protest, but it also expanded its thematic range, showing that Black art could be both political and universal.

The Black Arts Movement: Literature as Revolution

The 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of the Black Arts Movement (BAM), led by figures like Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, and Haki R. Madhubuti. BAM positioned art as an instrument of revolution, rejecting assimilation and embracing a proud, militant Black aesthetic.

Poetry became the dominant form of the movement, often performed aloud to connect directly with communities. This era emphasized African heritage, oral traditions, and calls for liberation. While some critics argued BAM’s separatist tendencies limited its reach, its influence on spoken word, hip hop, and later generations of writers is undeniable.

The Era of Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Maya Angelou

From the late 1970s onward, African American women became some of the most celebrated voices in literature. Toni Morrison’s novels—such as Song of Solomon (1977) and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved (1987)—wove together history, myth, and psychological depth to explore the traumas of slavery and the resilience of Black communities. Morrison also worked as an editor, championing other Black voices.

Alice Walker’s The Color Purple (1982) gave voice to marginalized women through a narrative of pain, healing, and empowerment. Maya Angelou, through her autobiographical series beginning with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), blended poetry and memoir to inspire readers across generations.

These authors expanded global recognition of African American literature, winning major awards and shaping curricula worldwide. Their works placed Black women’s experiences at the center of American letters.

Contemporary Voices: Diversity, Experimentation, and Global Reach

In recent decades, African American literature has grown more diverse, experimental, and transnational. Writers explore not only racism and identity but also themes of technology, migration, sexuality, and futurism.

Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning The Underground Railroad (2016) reimagines the historical escape network as a literal subterranean train, blending history and magical realism. Jesmyn Ward, twice a National Book Award winner, writes about rural Black communities in Mississippi with compassion and intensity. Ta-Nehisi Coates, through both nonfiction (Between the World and Me, 2015) and fiction (The Water Dancer, 2019), has brought fresh energy to political and historical discourse.

Contemporary African American women continue to push boundaries—Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half (2020) explores racial passing and identity, while Roxane Gay’s essays and fiction challenge narratives around feminism, body politics, and sexuality. Meanwhile, younger authors like Jason Reynolds and Angie Thomas (The Hate U Give, 2017) connect directly with young adult audiences, addressing police brutality and social justice.

Importantly, African American literature today has global resonance. Writers tour internationally, are translated into multiple languages, and influence diasporic conversations across Africa, the Caribbean, and Europe.

Themes Across the Ages

Across its evolution, African American literature has consistently emphasized:

Resistance and resilience: from slave narratives to contemporary protest fiction, the fight against dehumanization is central.

Identity and visibility: whether through Ellison’s “invisibility” or Morrison’s explorations of memory, the literature insists on recognition of Black humanity.

Community and heritage: oral traditions, folklore, and family stories form recurring motifs, connecting generations.

Innovation and experimentation: from spirituals and jazz rhythms in poetry to speculative fiction, African American writers have expanded the very definition of literature.

Impact on National Identity and Global Conversations

African American literature has helped shape the American national identity by forcing the country to confront its contradictions—slavery and freedom, democracy and exclusion, prosperity and inequality. It has broadened the canon, ensuring that U.S. literature reflects the fullness of its people.

Globally, African American writers have become ambassadors of cultural memory and creativity. Their works resonate with struggles against colonialism, apartheid, and racism worldwide. In classrooms from Lagos to London, Douglass, Hughes, Morrison, and Adichie (in conversation with African American peers) speak to universal quests for justice and dignity.

Conclusion

The evolution of African American literature is not simply a linear story from slavery to freedom; it is a tapestry of voices, genres, and themes that continue to expand. Each era builds upon the previous, producing a legacy of resilience and creativity. From the witness-bearing of Douglass and Jacobs to the imaginative re-creations of Whitehead and Bennett, African American literature remains vital—reshaping how America sees itself and how the world engages with ideas of race, identity, and justice.

The story is ongoing, with new writers emerging each year to challenge boundaries and redefine what it means to tell a Black story in America. In this way, African American literature is not just a record of the past—it is a living conversation with the future.